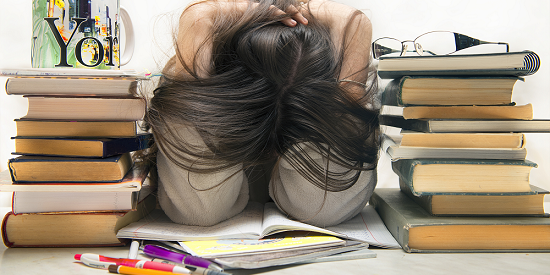

When a bright and high-performing child suddenly starts struggling to cope with burnout and anxiety in the final year of high school, it’s time to take a stand against a system that can take its toll on health and happiness in the household.

I’ll be honest, I was unprepared for my elder daughter’s matric year. Sure, we had the books and the stationery, and the new blazer with its candy-striped braid. On the surface, at least, we were prepared.

I’d reassured her, after a gruelling Grade 11 year, that matric was going to be different – certainly that’s what I remembered.

That matric felt largely like marking time, an endless rehashing of work already completed, and a seemingly limitless supply of past papers from our Afrikaans teacher, who drilled us so well that 17 in a class of 22 got A’s that year.

Come the end of March this year, however, I was faced with an almost 18-year-old who was completely and utterly burnt out: seeing a psychologist weekly, on anxiety meds under supervision of a psychiatrist, seemingly permanently chained to her desk often to the early hours of the morning, and with not much of a life outside of her schoolwork.

And, as they say in those annoying TV ads, that’s not all! Every other evening saw me spending an hour or more with a copiously weeping child, as I did my level best to calm her down enough to tackle just one thing on her list – which she often did through more tears.

I should point out that this is not a child who has ever struggled at school. She’s bright, hard-working and organised. She fired me from helping with homework in Grade 1, and has developed her own very efficient system of getting her work done – on time, and at a high standard.

But she had reached the point where the volume of work expected of her was more than she could cope with. Eight pages of questions on an Afrikaans set work, expected by the next day. A massive research project with not nearly enough library access to proper sources. Two to three tests on a day. Deadlines, deadlines, deadlines coming out of her ears.

It was school, homework, sleep, repeat – through a constant mist of tears. By the end of March she was sick – and beyond tired. She had an increasing pile of tasks she just couldn’t get to because she was prioritising the things required for her matric portfolio – and leaving the rest undone to collapse into bed at night. And when she looked up at me, her face pale and eyes brimming with tears and said, “I just want a weekend,” my heart nearly broke.

The cure for burnout is rest – like many things it’s simple, but it’s not easy. Because there are things that are required in matric year, which simply have to be done just to gain matric exam entrance. But there are also many things that don’t strictly have to be done. Yet they are assigned anyway, and the children are just expected to cope.

So, reluctantly, I had to get involved, because the truth is that no matter how much a school tells you that they want pupils to learn independence, often they only really listen when a parent tells them what the child has been saying all along. Often the children’s protestations only get them so far.

But to give the school its due, once I had fired off a few emails explaining what she would and would not be handing in, and by when – and the reasons why – the teachers were amazing. When I took her out of school for two days when a school sporting event precluded lessons, they allowed me to do so without a problem.

That gave her an extra two days to sleep in a little, catch up on some work at a pace that suited her, and rest as much as possible in-between. She’s not cured, but hopefully the school holidays – despite the work scheduled for what should be a rest period – will provide her with time to gather her breath, her thoughts, her sanity.

For the rest of the year, however, I will be prioritising my daughter’s health over her teachers’ demands. And that means she will be resting when she is tired – not when it’s 2am and she’s finally finished X or Y. And if that means she misses deadlines, then I will be that helicopter parent writing sternly worded emails. And when my younger daughter gets to matric in a few years, we’ll be doing things very differently.

Because these are my children, and I want them to be healthy and happy – and get the matric result they are capable of achieving. And I don’t think doing well enough at school necessitates losing yourself along the way.

After all, it’s only school – it’s just one small stepping stone to a much bigger life. But you can’t step from one stone to the next if you’ve lost the ability to balance.

Leave a Reply