Half a century ago this year, one of the most momentous events in the history of humankind took place beneath the bright lights of an operating theatre at the Groote Schuur Hospital in Cape Town. The first human heart transplant.

While the dynamic Dr Christiaan Barnard would later downplay its significance, by insisting that “die hart is net ’n pomp”, the operation was seen at the time as a giant leap in scientific knowledge, equivalent to the first manned missions to the moon.

It may be true that the heart is just a pump, but it is the very engine of life, and those who tinker with it to save and improve people’s lives are pioneers and heroes.

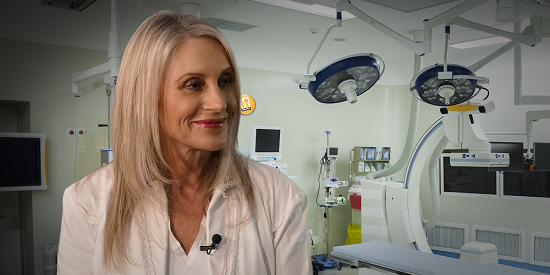

Meet one of them: Dr Susan Vosloo, the first female heart surgeon in South Africa. She was only in her early 30s when she performed her first heart transplant, and she has since earned global acclaim for her work in the field, specialising in life-saving surgery on children as young as six months.

Dr Vosloo sat down with Ruda Landman for a heart-to-heart chat in the BrightRock studio. What does it take for a young girl, whose primary interest in life is sewing, to become one of the best heart surgeons in the world? Watch the video to find out.

R: Hello, and once again a very warm welcome to The Change Exchange, where my guest today is Susan Vosloo – South Africa’s first female heart surgeon. And she operates mainly on children, heh Susan?

S: That is correct, yes.

R: How did you get into medicine in the first place? What did you want to be when you were a little girl?

S: I think even as a small child, I always wanted to do medicine. My father was a doctor and he was specialised in orthopaedic surgery. Sometimes I think he would have liked me to do orthopaedic surgery, because he always used to say you don’t really have to be strong, you just need to know how to do something, because he was fairly small. So I would say since I was a child I always wanted to do medicine.

R: Why? What was your … What did your father symbolise, if I can put it like that? What did he think? What did the doctor do?

S: I think I used to go with him, always. On a weekend, when he went to the hospital, I used to go with him, used to walk with him, he used to explain things to me and he was always … it just appealed to me, I think? It looked like he was always doing something good for his patients. The nurses liked him, his colleagues liked him and he always enjoyed what he was doing. We, as kids, saw quite little of him because he was working quite long hours, but I think he did set the example that I probably followed.

R: And then, how and when did you decide heart surgery?

S: I didn’t really decide that initially. When I was ten, the first transplant was done by Professor Barnard. And we were – I remember it so well – we were in Mossel Bay having a December holiday when the news came. And every next news bulletin we would switch the radio on and listen to the progress. And at that stage I had no idea that I would do that one day, and over time when I started doing medicine I quite liked surgery … I used to do a lot of sewing when I was at school. I used to make all my own clothes … I quite liked practical sewing. I wouldn’t crochet or anything like that. If I made something, I made something that is useful and I used to wear all the clothes I made. And maybe that played a role. And during …

R: I thought you meant you liked sewing up after the doctor had done the operation?

S: Yes … That I also did. I think at university we rotated through all the different specialties and some things you find more interesting than others, and I always thought in surgery you need to be a bit of a physician, you need to be a bit of a paediatrician and that’s what I really liked most.

R: Can you remember the first time that you actually held the scalpel?

S: You know, as students … I studied at Free State University. As students we did a lot. First, not so much cutting or using the scalpel, but we used to work in the trauma unit and we used to suture a lot. In other words, in those days there were more knives than guns, so there was a lot of lacerations, car accidents and so on. It was all very exciting and quite rewarding, so we had a lot of practical experiences as students. I think for starting to actually do procedures, that really came later. But one had many opportunities of being involved in surgery, and assisting the primary surgeon, even as students. I think my … The first operations we really did that were at all meaningful was caesarean sections. And sometimes 25 babies were born a night if you were on duty, and a few were caesareans. And that’s the really first relatively major surgery any student does.

R: When did your interest shift to children?

S: That came later. When I was at university, I wanted to do surgery. At the time I thought I would do vascular surgery, because it’s really clean and neat and the results … it always looked so beautiful to me. And when I went – I went to Johannesburg and as part of the first year of training in surgery I rotated through cardiac surgery …

R: Where was this? At Bara?

S: No, at that stage it was at the hospital called JG Strijdom …

R: It’s now Helen Joseph.

S: It’s now called Helen Joseph, and Rob Kingsley was the surgeon there. I was very lucky, as a very junior trainee, to get many opportunities to do things, so I would like open and close the chest and put the patient on bypass and so on, and I quite liked that. And he said if you like vascular surgery, why don’t you rather do cardiac surgery? And then I thought well that may be quite interesting, because in those days it was very common to do coronary artery bypass surgery. It was the most common operation in the world. Today it’s far less, and that’s basically suturing small vessels to each other, and …

R: Is that what vascular surgery is?

S: Vascular surgery …

R: Blood vessels?

S: Blood vessels. Vascular surgery is connecting blood vessels … Or not connecting … Working with blood vessels. So for instance, when you have an abnormal blood vessel like an aneurysm, that’s like the ballooning of a vessel, the surgery to repair that is vascular surgery. When there are blockages in any vessels like to the legs or to other organs, and also in the heart, which is what we used to do, then it’s vascular surgery to use vascular grafts. Like in those days, we used veins from the legs and then connected the vein before and after the narrowings, and that is why it is called bypass surgery.

R: So what is it like to stand there looking at someone’s heart beating?

S: Uhm, I cannot …

R: Does one get used to it?

S: I think you do. You do not really … I don’t think you really see the heart beating as such. One’s more focused on what the abnormality is, that you need to address, and what are the precautions that you need to take that when you correct the abnormality, that the organ function is still normal, or adequate to maintain the circulation.

R: So you trained yourself to look at it almost technically?

S: You do. You do, actually. But you do also have to keep in mind that this structure belongs to an individual and that whatever procedure one does can potentially harm an individual or it will give enough of an insult for someone to recover from once everything’s been corrected. It’s not like you correct something and it’s all done. There’s wounds that need to heal and so on. Those things take time.

R: So tell me about deciding on children?

S: Then … At the end of that year, I came to Cape Town. And when I arrived in Cape Town, I was first placed at Red Cross, and somehow for most of my training I spent a fair amount of time at Red Cross. And I found it very interesting. In our days we were very lucky that we did a lot of operating, we were allowed to do quite a lot, so that by the time we were finished with our training we could actually do the work. Nowadays I think with the lack of resources and so on, the numbers of cases have reduced a lot, and many trainees finish their training with limited practical experience, which we were lucky that we were in that period.

R: Is a child as a patient different? In your experience of it from an adult?

S: Yes, a child is very different. It’s a little bit … A child cannot communicate, always. A small baby cannot communicate. A child has difficulty expressing how they feel, and sometimes if they are scared, they don’t have a way of showing it. The other major difference between adults and children is that you interact with an adult patient. So you interact primarily with the patient, and the family is in a way – if one can say so – secondary. With children, you interact with the parents and often also with grandparents. So a lot of the care of children is really your communication with the family, and also supporting them in times that they find traumatic or stressful. The child is not your primary contact.

R: Does the fact that you are a woman make it easier, do you think?

S: In some ways it does. I think people do perceive women as more sympathetic, and I think it’s easier maybe to relate to parents. On the other hand, people are sometimes surprised that a woman actually can do their work. So it cuts both ways.

R: Have you found that it is still a man’s world? I mean, the first female heart surgeon?

S: I never actually felt it while I was training, because I was never shy to work. I had some male colleagues who were, like, leaving at the first opportunity, so I was always prepared to work. So from that aspect I did not feel at all threatened. It actually was … I was prepared to do that. As I grew older, you start meeting more resistance. For instance, I was planning to stay in academic medicine, it was, like, I really loved it and I enjoyed it, I enjoyed the work, but I never wanted to be the head of the department. So I didn’t want to be a manager. So I never had that sort of aspirations, but I did have experiences where the person who then becomes the head of the department is like your peer, and they make life difficult for you. So in the end it became rather unpleasant and I actually left academic medicine and went into practice, which was …

R: And you think that was because you are a woman?

S: I cannot say. I mean, it may be other factors, but I cannot say my male colleagues were treated the same way, and I also can’t say that I would have allowed my male colleagues to be treated the way I was treated at that time. And it did make a difference in how you decide what to do forward. But like any setback, there’s more opportunities in setbacks than disadvantages.

R: Where did you go?

S: I then went … I then … Initially I had a part-time appointment and I went into practice in Cape Town at the then-called City Park Hospital. And that’s where I still am nearly 30 years later.

R: Did you ever meet Professor Barnard?

S: Yes, I met Professor Barnard many times. I did not meet him while I was studying … When I started in 1984 at Groote Schuur, Red Cross Hospital, was the year after he retired. At that time he went to the United States to Oklahoma and he came back around 1988 when I had already finished my training. That’s when we met, and we had quite a friendship in his post-retirement phase. He had a foundation in Austria – The Chris Barnard Foundation – and he brought kids from Eastern Europe and Russia, under … as part of the charity work of his foundation. I did the operations, so he brought the kids and it was great fun. And he used to be quite involved in the Organ Donor Foundation in the middle … Actually in the 1990s, and I was very involved with the Organ Donor Foundation and we used to have some events and he was always kind enough to participate and be the guest speaker and he definitely drew interest and it helped a lot to raise funds for a good cause.

R: So he would lend that star quality?

S: More than that. He was absolutely … he was wonderful with things like that. And he was a wonderful personality – a great sense of humour – I’m sure you also met him?

R: I never met him, no.

S: You never did? What a pity. He was absolutely wonderful. He could relate to anybody. He could be kind to anybody. There were a lot of anecdotes while he was working that he was sometimes difficult to work with, but it’s not something I ever experienced.

R: You’ve also allowed television cameras into your operating theatre and into the whole process of finding the donor, connecting with the family, putting that together which is a deeply emotional thing. How did you experience that?

S: Well, Anton’s cousin and his partner has a film production company, and they did various documentary programs and they wanted – some years ago – to do a documentary on transplantation. And at the time, we had a brother and sister – it was in the early 2000s – a brother and sister who were both waiting for heart transplants. And they did a program about them, and a lot of the program is actually not involving us or being in theatre at all – they used to visit the family, spoke to them, how they felt, and they did this program which then covered the journeys of these children. And more recently they asked if they could do something like that again, and we agreed to do that. So very little of the actual program involves cameras in theatre, and because they are quite discreet and because they are there without you in a way knowing they are there … So they would be there, but when you work, it’s quite focused. So we don’t really interact much with people in the room when we’re doing the work, but of course when we’re finished we would speak to them, give a bit of information and so on, and I think the program has been … They’ve been quite satisfied with it, but my role is fairly small and they haven’t been invasive at all or disrupting in anything.

R: It so depends on attitudes and so forth.

S: Exactly. And we’re used to people in our theatres. We often have students, colleagues coming … I sometimes … It feels like there are a bit too many people around, but it is our way of sharing what we are doing and for me it’s no problem to in a way … I wouldn’t say ignore them, but that’s exactly I do.

R: You carry on with what you’re doing.

S: I just say beforehand, that we can show this and this what everyone does, and you’re welcome to ask questions, but once we work, I don’t want to actually … I don’t want movement in the sort of your visual field, because it’s quite disturbing and people then know maybe we ask questions afterwards. We have a way that we allow people, but we don’t let it affect what we are doing.

R: Your husband, Anton is an anaesthetist.

S: Yes.

R: Where did you meet and when did you decide that this was a partnership that could be more than professional?

S: We met in 1982. I was working in Bloemfontein where I studied, and I was working in intensive care. In those days, were the early days of intensive care. And after my year of doing that, my professor offered me to come to a conference in Cape Town. At that time Anton was working in Johannesburg, and he came to the same conference and we met at this conference. He was a born and bred Capetonian – he was born, went to school, went to university and travelled a lot before and during his time that he specialised. He was interested in cardiac anaesthesia. In those days he went to work in Johannesburg because there were opportunities for him, and that’s the same time as I went to Johannesburg to start surgical training. And somehow during that year we sort of got to know each other and at the end of the year he came back to Cape Town and asked me if I would like to come with … I must say, I was a bit … I wasn’t certain at the time, but I thought why not. And if it works, it works. If it doesn’t, then it’s just one of those things. And I’m still here!

R: What is it like to work together and then share the rest of your life?

S: For me … Although we work together, it’s not like there is a personal relationship at work. At work I have my responsibilities, and he or his partner – who also works with me – have their responsibilities. So if I have to think last week or even yesterday who was my anaesthetist, I wouldn’t know, because they have their own roles to play. Where it’s helpful, is for instance when you, if I go away. Sometimes I’m often out of town – often sometimes out of town. Then at least I can … My phone is always diverted to him if I cannot answer for any reason. So it’s a nice backup to have, so at least even if anything happens or somebody rings me or so, it’s never that the phone goes unanswered. So from that point of view the professional relationship is very useful. And it also helps to understand that you sometimes … The days are a bit long, sometimes you come late, but it works both ways.

R: How does one keep the relationship fresh and solid if you both work such long days and you have such busy lives?

S: Ja, we do, but we … I think it’s just the way things happen. We go home in the evening, we often go out in the evening, maybe we have a meal together, we’ll do something with the children, or … When the kids were small they used to go to my mother for one evening a week and we just make time to do something that we enjoy.

R: That’s quite a practical thing, one needs to make time.

S: We always, when the kids were small we thought that one night a week we will definitely see all our friends and pick up all the social connections, but you actually don’t do it because sometimes when the kids are small they so dominate everything that you’re quite often happy just to go home and actually have an uninterrupted conversation.

R: And tell me about the kids. You thought that you would never have children of your own?

S: Yes, I thought so. When I was 40, I thought, you know, maybe you just missed the boat. And then I went …

R: Did you try?

S: No, I didn’t actually do anything. I thought it will happen, or it won’t happen. But when I hit 40, I thought I was a bit disappointed and then we discussed it and then I went to see somebody and went through 13 attempts of treatment, which is quite traumatic, because every disappointment affects you a little bit, but it helps if you can just go again, then it doesn’t … It’s just trying again. But then after 13 times and a few serious complications, the time came to call it a day. And then we were extremely fortunate. My brother had two boys – they were at the time sort of seven to nine years old – and his wife … And we had a little, she offered to be a surrogate mother …

R: Did it just come from her?

S: Yes. I was very surprised because she’s a non-medical person and I never even considered that. We sort of did think of adoption, but Anton wasn’t keen on that because he knew people that adopted kids and they were not happy. You know, it didn’t work out so well. I knew people that adopted kids and they were extremely happy, so I was quite comfortable with that. He wasn’t. And then somehow in a conversation this came up. We discussed it with the clinic or our colleagues who were specialised in that, and they thought it was a good idea and it worked the first time. So we were very fortunate and privileged to do that.

R: Can you remember holding your girls for the first time?

S: Yes, actually when they were born they were … They lived in Johannesburg and I went always when there was an antenatal visit, we went together. And when it was towards the end of the pregnancy she came to Cape Town and she was at the time studying for exams, so it was good to sort of take time off work and study. And the kids were born in Cape Town. They were delivered by a very good friend of Anton whose child is his godchild, and we decided beforehand he was going to take the first baby, and I was going to take the next one, so we actually could hold them when they were born. My brother was there to support his wife and for us it’s been a wonderful, wonderful experience.

R: How did they change your life, if at all?

S: Well, they do change your life. I think the logistics of a normal practice with unpredictable working hours was challenging. I always had somebody for the kids. So I had somebody in a way to represent me at all times. My mother … My brother and sister are twins and my mother offered to come and look after them for the first three months. So in that time I worked a little bit less, and she was there so I came home earlier and spent a bit more time at home. And since then they had an au pair for the first year or two and then they had a girl for more or less from when they were two years old until they finished primary school. The same girl looked after them and she was wonderful – she did everything what a mother would do in terms of running around, feeding, dressing and so on. And we just had the pleasure of their company and that was great.

R: And now they’re 16?

S: They’re 16. When they finished primary school and I said you can’t have an au pair until get married. They were very disappointed! The first few months of planning and not having somebody at your service was a bit of an adjustment, but they’ve actually adjusted extremely well and they’re very independent and they’re great company. We enjoy every minute of it.

R: And tell me something about your home? You lived in an apartment for the first while? First part of their lives? And then you chose to go and live in a home? What attracted you? What sold that house to you?

S: Actually we, our house, we live in a house which we had long before the kids were born. Where we live in Cape Town, in Green Point, it’s a little against the hill, so the houses there have steps and when the kids were born I also bought an apartment in the Waterfront, which was just developing at the time. And that was on one level. So we chose where we lived to live close to where we work, so the nature of the work we do is such that you cannot really be far away, because anytime anything unforeseen can happen. Sometimes one just wants to make a little visit and it’s not like you want to travel twenty minutes, half an hour late in the evening just to see that everything’s okay. So we chose homes close to where we’re working, which today we’re very grateful because the traffic has become an absolute nightmare. So when the kids were born, we lived in our house, and we then, when they were about a year old, when they started walking, this apartment was finished and we went to live there for four years and they started to walk and swim and so on, and then one day we decided now we’re moving back to our house and we’ve been there ever since.

R: What’s the best thing about that house?

S: The house … I think the views. We have magnificent views over Mouille Point and the new Cape Town Stadium, the Waterfont, Robben Island and the other major attraction is that it faces north. In wintertime it’s nice and sunny, and in summertime it’s cool enough, but the major attraction is the convenience being … Not having to spend too much time on the road and traveling.

R: Susan, thanks so much for making time. It’s in the middle of the day and I know that it’s a special concession, so thank you.

S: I so enjoyed it! Thank you very much.

R: Until next time. Goodbye.

- This interview first appeared on the Change Exchange, an online platform by BrightRock, provider of the first-ever life insurance that changes as your life changes. The opinions expressed in it don’t necessarily reflect the views of BrightRock.

Leave a Reply