With its top-secret shebeens, captured parliamentarians, and a cast of knockabout characters that includes Oros, Juju, and Shaun the Sheep, South Africa is a dream state for cartoonists, stand-up comedians, and satirists.

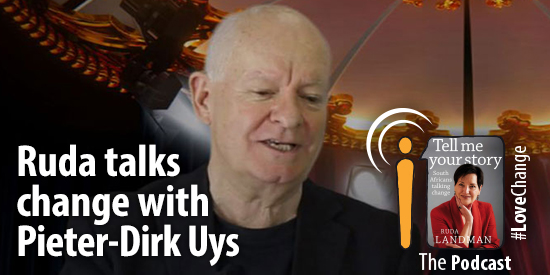

And the greatest dream merchant of them all, the one who has kept us laughing and thinking through more than four decades of change and upheaval, is Pieter-Dirk Uys. In close collaboration with his alter-ego, Evita Bezuidenhout, Pieter has left no sacred cow unbraaied, and no social or political taboo untackled, as the court jester of a nation that is constitutionally entitled to laugh uproariously at itself.

Now in his 70s, Pieter is still going strong, and as for Evita, well, of course, she’s ageless. In 2014, 20 years into South Africa’s democracy, Pieter-Dirk agreed to his most candid and confessional interview yet to celebrate his partnership with Evita in the frontline of our funny-peculiar nation. Listen and enjoy – it’s the hottest one-man, one-woman show in town!

Transcript:

R: Hello everyone and our guest really needs no introduction … Though you’re in a different persona today. This is the real Pieter-Dirk Uys!

P: This is the most difficult one I’ve played for a long time. The others are easy. I had to create Pieter-Dirk Uys, I think I’m more confident now.

R: I always say to students who want to present, that that’s what presenting is. That you play yourself.

P: Absolutely. And it gives you the confidence to know that it’s a character that you can blame.

R: [laughs] Okay, I’ll remember that. When did you know that you want to perform?

P: First of all, I come from a family of performers. I have a mother who was a concert pianist, my father a concert pianist and an organist and a choir leader, my sister a pianist … We sang … I sang as a boy soprano … I remember turning 13 and looking in the mirror and saying: “Breek jou bliksem, breek!” Because the voice didn’t break. I had to wear short pants all the time. And I did sort of perform, but it wasn’t a performance, it was showing off. We did concerts on a Sunday, with the two grannies. The Afrikaans granny, and the German granny. And then Tessie would do something and I would do adverts for stockings … put my leg through the curtains … I don’t know what started there, but …

R: Where did you live?

P: In Pinelands, in Cape Town. And then we would put the little hat around to collect money for the SPCA. And I had just had my appendix out at the St. Joseph’s hospital and I fell in love with St. Joseph’s, The Nuns! They were so sweet to me. So on the Sunday we collected money, and Ouma Uys said: “Is dit…” She always had to speak English because the German granny het gesukkel met Die Taal. “Is this for this little animals?” And I would say: “Nee Ouma. These are for the nuns.” And then sy het haar geld terug gevat! She took her money back. And that’s I think around the time that she said to me: “Pietertjie, you must remember. The English are your arch enemies, the Jews are the thieves and the Catholics are the Antichrist. Finish and klaar.” The blacks were never a problem.

R: Neat categories.

P: Very neat categories and that was the slogan and ja, ouma het my so geleer. No, so the performance really … I don’t know … It wasn’t an ambition, really, to perform.

R: So how did it happen?

P: Well I’ve always loved performers. I have always been a Stage-Door Johnny, I’ve always loved actors and actresses and admired them and movie stars like Sophia Loren, who has been my love all my life. And then I went to university to become a teacher, because I wanted to be a teacher. I had one great teacher at school, Miss Aloise Nel, who really gave me the foundation of my life when she said: “You must write a poem.” Ek was in ‘n Afrikaanse skool. “You must write a poem.” And I said: “Miss, I can’t.” And she said: “Yes Pieter, you can.” And I said: “Miss, really I can’t write a poem.” And then she said: “Pieter, you can do anything. If you believe in it and you work towards it, you can do anything.”

R: What an amazing foundation.

P: Incredible. And I did a very good first year at UCT, I was pretty boring. I had just learned how to smoke cigarettes … so né – butch! I remember at the Clifton Hotel, having a beer. I hate beer! And all the surfing boys were there en ek sit met ‘n sigaret and they all flick and the sigaret gaan na Australië and I would [squirt noise] and so it didn’t work well. And then my parents said they’re going to send me overseas to see the world, as a present. Which was fantastic! 1966. And I went with a boat over to London and a friend of the family took me to the theatre to see Laurence Olivier in Othello. Louwrens Olivier! And I thought: “This is a white man, blacked up. We’ve got so many in South Africa, why didn’t they bring any of ours here?” And I just think that’s where something clicked about the excitement of being a member of the audience. And then, when I came back to South Africa after this, like, two months away, back to university for my second year, I met in the canteen over my slap chips at UCT when we were registering, this girl with a beret and sunglasses and cigarette holder, Phyllis Punt, aktrise. Drama student. And I looked at her and I thought: “Hell, how do you look like that. I want to look like that. What do you do?” And she said: “I’m an aktrise.” And so I followed her to drama school, and that’s where I started at drama school. And then within a week they said to me: “Oh Pieter, you don’t really have talent. We don’t think you have talent as an actor, become a stage manager.” And I said: “Yes.” Because you believed older people in those days, they always knew better. And that was the best training I could wish for! I was trained in the alphabet of theatre. Everything I can do, out of necessity, I learned it because that was my job. And now, after forty something years in the theatre I still set up my stage, I write my material, I make my dresses and I wear my dresses … So that was the greatest background, that’s where it started.

R: And you’ve said, on your CV, that you’ve been self-employed since the seventies? How did that happen?

P: I said I’ve been unemployed since the seventies. The last time I had a job was in 1974, where I worked at the Space Theatre. I got R20,50 per week and we saved money on that, and the Censor Board came and they banned all my plays. They banned Karnaval, they banned Selle Ou Storie, and then eventually Die Van Aardes van Grootoor and Info Scandals and it wasn’t fashionable at the time. It wasn’t that people said: “Oh wow, let’s have the t-shirt and celebrate.” They said: “Don’t come near the house … Even my father threw me out of the house and said: “Jou kommunistiese, liberale … ” He was scared! Because everybody was scared! And especially my dad, and I think specifically being an Afrikaner and ‘n Christelike, deeglike … A marvellous human being, whose cousin was Doktor DF Malan … Okay, so that’s where the legacy slipped in …

R: Explains some things.

P: And so I had to become my job. I just literally, because even the money at the Market Theatre, I came with a new play and he said – he used to call me Petrus Poephol: “Petrus Poephol, I would love to do this play, but I can’t afford it. We lose money when you get banned.” And of course that’s the reality, it’s not that people say: “Oh, we’re going to do the play. To hell with banning, we’ll do it!” And so I thought well, I’ve got to be my own … I’ve got to be in charge of my life. And so I started with Adapt or Die, a one-man show.

R: How difficult was it on a practical level? Because one has to buy bread and milk? Not bread anymore, Tim Noakes has said no.

P: Listen, Tim Noakes, I like my bread. And my cat needed the milk! My cat got thinner and thinner. And really truly, it was a case of just … Let me do something. I couldn’t stand the fact that other people had told me no. As Miss Nel said: “If you believe in it and you worked for it, it can happen.”

R: So what was the first thing you …

P: The first thing was watching PW Botha on television … I had a little black and white set, which I really could afford. That was still a black and white set. I was still waiting for my Beta Max machine, which I couldn’t afford yet! And I switched the volume off, because who wants to hear that voice …

R: Sit dit af, sit dit af!

P: So I did it back to the TV screen. “Ons sal! Ons sal!” And suddenly the cat laughed. And I thought: “Hello!” And I thought: “Hang on, I don’t like any of these people. I don’t want to get involved with these people. They’re my family! I’m going to make fools of them, I’m going to laugh at them. I’ll behave like a 12-year-old, actually. Ek gaan vloek. Ek gaan slegte woorde gebruik.” And then my father, my pa, who eventually came to the shows … When I started making money he realised it couldn’t all be bad! Ek het hom gebribe.. I gave him a cheque every month and I said: “Go up the Amazon, go up the Andes, go wherever you like. Don’t criticise my politics, or else you will go to an Old Age Home and you will die alone without me, verstaan jy, Pa? My magtig, kind, natuurlik. But he didn’t like the way I used swear words in Afrikaans, but there are no swear words in Afrikaans, it’s poetry in Afrikaans! In English it’s very bad, but in Afrikaans is dit mooi. And Lizzie Meiring and I were doing a show at the Baxter in 1990 – dit was my pa se laaste maande voordat hy dood is. And he had a wonderful laugh! He always laughed two seconds before everybody else. And he laughed for the first three minutes and stopped. And I thought: “Kwit, pa is dood! What’s happening?” And I came home and he was sitting there with his glass of wine and hy praat nou Engels. When my father spoke English I was in real trouble. He says: “Why do you use that language?! You use these disgusting words – – die vieslike woorde! Ek word so kwaad, jy steek jou vinger in my oog en dan is ek blind en doof!” Hy sê: “Bokkie, gebruik daai vinger, kielie my agter my oor sodat ek lekker voel, en as ek wil sien wat vir my laat glimlag, gaan ek omkyk en my oog sal jou vinger vind.” In other words, don’t be obvious, don’t always go like that! Turn around, do this, play with the anarchy of what people expect and don’t give it to them. The anarchy of sex, the anarchy of politics, the anarchy of racists – every single thing that is a target. You can find a way of dressing it up and making it look like entertainment, and get people to laugh of the thing that they don’t want to think about. So that came from Pa as well.

R: That is such an interesting interaction!

P: Well you know, I just had to pave my own way, because there was no blueprint, there was no handbook … I mean, I had Robert Kirby as a mentor, meaning that Gosh, he was a powerful, incredibly vicious satirist who didn’t take prisoners. Now I became a copy of him, or I found my own alphabet, as well as Athol Fugard, who was at the Space Theatre as well. This great mentor, this great leader. I now became a second Athol Fugard, meaning a copy, or I find a different platform, which is humour. That’s where I found the humour.

R: But as your father said to you, there’s a very fine line between funny and offensive. And how does one find that balance?

P: Well you know, I really can’t tell jokes. I wish I could, I admire people that can tell jokes. I forget the punch line. I build up the joke and then I forget and “o kwit, hoe eindig die blêddie ding?” But the truth is funnier, and I learned through those years of apartheid that the targets – first of all, apartheid was NOT funny on any level, but the hypocrisy and the extraordinary blindness, jy weet: “Ons is Christene and we’re decent people.” And they were! They were. I can honestly tell you that I don’t think there were any mass murderers among them, which made them even more dangerous. I keep on saying Adolf Hitler was a human being, for heaven’s sake, don’t forget that, because that makes you frightened! A monster – you have a monster on television created by a scriptwriter. And it was for me so extraordinarily important to try and find the truth, but not lie, not add noughts for effect – – because on the stage you’ve got a lot of power – you can say 10 000 people have died. One person that has died because of bad politics is enough to make me angry for the rest of my life. That’s why I opened most of my shows during the seventies and early eighties in Bloemfontein, because I knew that if I told them the truth that they would listen, and if I lied, they would blêddie well kill me. And I spoke to many people that said: “Jirre jou klein bliksem, waar hoor jy dit?” And I always get the facts: “Well, this is the fact.” And: “Ja, nee, jy’s reg.” It was extraordinary. And so, of course, sorry, just to finish the thing about offensiveness. I want to offend everybody! But not all the time. It’s too exhausting. And I think to offend somebody, is actually important, because you suddenly make them listen. I’ve suddenly rukked their cage and they’re going: “Oh! What!” In other words it’s not about the way I think about it, So who has actually got the reality here? To demean people, to insult people, is off, I don’t do that. So that’s what I avoid like the plague, because you can also do that with ease, because of the power you have there. The red line of racism gets closer and closer every single day in our democracy. There was no such thing in the old South Africa, because it was politically correct to be a racist. So I had to be anti-racist in South Africa in those days. I couldn’t even call myself anti-apartheid, because it wasn’t about being anti-apartheid. It was about being against the status quo – there had to be an alternative. But humour is a great weapon of mass distraction. People don’t expect to remember what they laughed at, and that’s where I work now. Also now the definition: 49% anger, 51% entertainment.

R: Because otherwise they won’t come again. They will stop …

P: No I wouldn’t bother. You’ve got to be sexy, jy moet bietjie tiete skud.

R: Talking about that, the birth of Evita? Where did that come from?

P: Again, Evita was just a character. She was … first of all … she didn’t happen on a stage, she happened in a column … I had a little column in the Sunday Express in 1979, 1980. That’s when I had no work, and I was really panicking, and somebody, an editor on the newspaper, Koos Viviers, said to me: “Man, come on! Give us 100 words every week about the news and try and be funny.”

R: At about R1,00 per word?

P: At about R1.00 a word … it still is R1.00 a word, isn’t it? It was terribly important, I could feed the cat en alles. And so I did … and of course the info scandal was at full steam, so all those information things I have heard, not reading about it, because it was not news. Not hearing about it on television, because that was controlled. People would say: “Did you know about Eschel and this happened and Eschel flew people to Antarctica for a braaivleis en daar was dit en dat.” En die Smit moorde, all this darkness and that. So once a month in one of those four columns a month, I would do a column in Pretoria. I was at a party, and this Afrikaans tannie, who is the wife of an MP, a Nasionale MP, and say: “Skat, have you heard?” So she would come with that information that was sub judice and illegal and I would weave it into these 100 words. And after about six months of this, the editor of the newspaper said to me: “Just tell me something. How is it that you can write about things that I can’t put on the front page? Who is this woman? This Evita of Pretoria?” So the name came from him. It was just when the musical came out – of Evita. The Don’t Cry For Me Argentina.

R: Oh, so she didn’t have a name before that?

P: She didn’t have a name. She was just a Tannie. Die Afrikaanse Tannie. And so I read about Evita, who was Evita Peron, I got the book about Evita Peron – what a fantastic life! Jy weet, tert deluxe becomes Empress. What a beautiful blueprint for a character, because suddenly I thought here is a character! And so that’s where Evita started. Even the surname … I was being interviewed by Barry Hough from … ek dink dit was vir Beeld, destyds, Barry. En ons sit by die Market Theatre and he says to me … Hy’t mos gehakel, ou Barry. Ag siestog, die liewe man! And he said: “Hierdie E-E-E-vita van jou. Wat is haar van? What is her surname?” And I said I haven’t thought of it. And behind him on the wall was a poster, saying “The Seagull”. With Aletta Bezuidenhout, Sandra … Bezuidenhout. And to this day when I see Aletta, she says to me: “My magtag! When Evita Bezuidenhout happened people asked me if she was my mother. And now they ask if she is my sister!” So slowly but surely, people would ask me questions about this character, about her background. Does she have a family? So there came Oom Hasie. Does she have children? Daar kom die kinders. Does she have a job? There came the homelands, Bapetikosweti. And she was an adapt … met ‘n groot pienk hoed. She looked like … Ag man … Du Toit. Marie du Toit in Die Kandidaat, onthou jy? That pink scarf met die groot hoed, en daai wonderlike oë … en Marie, oh, wonderful! And there was Evita. And of course she came at the right time – she came at the time that the media needed a break from trying to hint at what was happening and not being able to, and they would put Evita on the front page when PW and Elise went to Europe for the first time to see if the world is actually flat. I had this wonderful thing … Nardus Nel – hy is onlangs dood, jislaaik, I was so sad to read that. He took these wonderful fashion pictures of Tannie Evita met al haar goed, and Rapport put her on the front met: “Tannie Evita neem mode saam met Tannie Elise oorsee.” And just suddenly the people started realising that they could actually smile and laugh, and of course, the greatest thing about Evita’s character was to this day – she has no sense of humour. No sense of irony. She doesn’t ever use bad language, she doesn’t blaspheme – and that’s okay. She can tell the truth – that’s fine. Maar moenie vloekwoorde voor die kinders sê nie. And so that is the key – if I cross the line, I lose her.

R: Tell me something – we’re talking about change on this platform. Going from Pieter-Dirk and you look in the mirror and there is Evita. What is that like?

P: Well it has to be careful, because she needs the respect of being believable. The theatre is a certain place where I can cut corners. If I’m on stage with my audience, and traditionally I never leave the stage because in the old days the police were waiting for me behind the curtains, so ek bly daar. Laat die donners vir my vang in die lig! And then I always did Noel Fine, my kugel, who always did my make-up while she was talking about her maid, Dora, and all that. And then of course I got all the basic Evita things on, and then just turn around and put on the brown wig and ‘kloeps’ – daar is sy. But when I’m doing her for a camera or for outside the theatre, she’s got to be very carefully done. The women must recognise this woman, and the men must forget the man. And if I can really convince Pik Botha that she is real, he still says: “Magtag, maar sy is darem … [inaudable].” And Nelson Mandela: “Oh, but you look so beautiful!” So I have got to … So I do boom, boom, boom and then I see her there – it’s usually when the hair is on. As age happens, I feel like … Joan Rivers would say: “Do a little tuck here.” So what does it feel like?

R: To find such a different person inside yourself?

P: I never think of that. I know she’s there, I know she’s there. I also know I don’t spend too much time on her. About 2% of my time. Because she’s got such an alphabet of information now – she’s been around for so long. And I read all the newspapers – it’s part of my … I suppose I’m a news-a-holic. So she’s now a member of the ANC – they really deserve her! I have to … she has to be in a position of power. After democracy, she lost her power. She lost her homeland. She went into the kitchens, which is also power. She cooked for Madiba, she cooked for Thabo, which is difficult because the food was always cold because he was never here. She’s very careful of all the Mrs. Zuma’s – they’ll never be in the kitchen together. All of them want separate kitchens want hulle baklei onder mekaar! But now she’s with the ANC and that’s also a very important place because people are like … Why? And I say it’s because that’s where the power is. It’s not in parliament, it’s in Luthuli House. And her grandchildren have said to her: “Gogo, what are you doing to protect democracy so that when we need it one day it will be there?” That is a very important part of where Evita’s got to be. She still tries terribly hard to be the designer democrat – she says: “Children don’t have colour, children are innocent, pure like angels!” Until they start stealing, then they become black! But before that … die gehoor … Even Oprah Winfrey had to laugh the first time, you know. So Evita’s led by politics. If Jacob Zuma wants to make her the ambassador to Mongolia, then she’ll have to go. I’m just glad that he doesn’t know where Mongolia is! My respect for her is very, very sincere, as my respect for all the characters.

R: So do you think that humour can effect change, or do you draw your ammunition from the change?

P: Interesting question, because I haven’t got an answer for that. I’m scared of that answer. I’m very scared when people say: “How do you feel you’ve changed things in South Africa?” And I say: “Don’t come to that, I’m an entertainer! All I want is for you to give me your time, your money is nice, but your time much more valuable. Four hours? At least to bring you to my theatre in Jo’burg, you’ve got to first get home from one hell of a hard day of work – the last thing you would not want to do is not have a whisky and have to go out again. Then you’ve got to set the burglar alarm, you’ve got to feed your Rottweilers, you’ve got to load the gun, you’ve got to reverse the 4×4 out of the driveway hoping the burglars don’t run in! You’ve got to get into the traffic, you become racist within 40 seconds, you get into the theatre, you park your car, you kiss your car goodbye. Then you’ve got to go into the theatre, you sit down and then what happens? Does your life actually change because you’ve forgotten about your fear? Or are you bored? And you know how we bore people with bad theatre? They never come back. So it is a terribly important reality that every performance is my first and my last one. I hope I can have another one afterwards, but if I’m not 100% on this one, I won’t have another one in the same structure. And so the change in my country, of course, changes my whole focus on where my material comes from. Where the apartheid era forced me to be on stage, and speak for the majority of South Africans who had no voice … it was a very simple target. It was apartheid … apartheid was good against evil. Black against white. There was a light at the end of the tunnel. I never thought we’d get away with apartheid, let me tell you, and we did. Now in the democracy, I don’t speak for anybody except myself. It is very personal, it is my opinion, everybody had the chance to stop me and say you’re a racist, I don’t agree with you and they’re right to say that because they also have an opinion. I must sometimes rethink where I am as things change around, but unfortunately my disappointment is so huge at the moment, that the party – the Freedom Movement that I really supported and voted for – has gone into politics as usual. I mean – Oh Lord! And there’s no light at the end of this tunnel. I just think – I’m 69 years old, I’m terribly relieved that I’m not 19. That’s why I’ve got to go to the 19 year olds and I spend most of my time doing that, going to the schools with a free show, because otherwise they wouldn’t let me in. But they let me in. What are you going to do and I say: I’m not going to tell you.

R: And how do the kids respond?

P: Incredible! I’ve been to over a million kids and more than that in the last 12 years. The inspiration for me is so enormous – I’m usually so exhausted when I drive through the Vaal Triangle, trying to find something that is not on the map, trying to go to a community and a township that has potholes that puts Jo’burg to … you know, Jo’burg has like big roads compared to these potholes. And you see this big building and you know it’s a school, because it looks like prison and you see the kids just sitting around because I’m an hour late. And they think: “Ag, it’s another white person that doesn’t bother to turn up.” And I think: “Oh my god.” And I stop the hired car and lock the hired car and o kwit, almal staan en kyk en ek dog: “My ouma was reg, ons Bloedrivier praat vol, jy weet.” And they come towards me and they pick me up and they carry me into the hall, and they put me down on the stage and they sing for me for 20 minutes, and then I must really give them a life changing experience of me coming to them, and I am over 50 then, and they’re under 20 and I say to them: “Okay, let’s make a deal. You make me feel 16, I will make you feel 24.” And then the playing fields are level. And I just tell them: “Do not allow your fear to lead you away from where the open door is, because it will.” Confront your fear, find out exactly why you’re frightened. And the major thing that kids are frightened of is they’re not going to get a job. And I say to them: “You will never get the job you want. You will always start working for somebody else and end up working for somebody else. Become your job now! How old are you?” 12. “What do you want to be?” I want to be trapeze artist. “Start tomorrow. Within five years you will be the best in the country and after 10 you will be the best in the world. You don’t have to belong to the ANC and you don’t have to be black or white anything. You are your own boss. That was my experience of my life and that’s the sharing I have and my goodness, you know, I’m such an optimist about this country! I am so thrilled and excited about where we are going, if we can keep our young people alive with information and with courage and with respect.

R: That leads us to your AIDS work. How did that start?

P: Well it started purely because I suddenly realised I was being dishonest. I was actually not confronting my biggest fear. During apartheid my biggest fear was being a white South African, being an Afrikaner, being Christian, being a decent human being and being responsible for every single thing that was happening under the name of apartheid. And I can never say that I stood aside, I am totally responsible. HIV/Aids was … I was losing friends, I was standing in the doorways seeing my 19 year old friends who look 700 years old, saying: “Come here, come here. I’m discussing my funeral.” Oh my god!

R: What year are we talking about?

P: 1985, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90s – it was 15 years of denial. Then Thabo Mbeki actually slapped me into sense, when he suddenly came up with this … if he said it or not, I’m not sure, but he stood for the concept that HIV does not lead to Aids. And I thought: “Hey, hey, hey! Okay. What do I do now? I must put it in my show. How do I put it in my show? Where do I go? How do I start? I’m going to do a little show for schools.” I knew a few schools around the Cape that I’ve been to, for various things, and I said: “Come, I’ll bring Evita to talk about a few funny things. And I’ll go and I’ll talk to them and Jirre, dit was moeilik. The first school that I went to was an Afrikaans school and it was a total disaster. Me, saying those things to an Afrikaans school, in 2000 was already … and I went to have tea afterwards, half the staff walked out.

R: How did you do it? Did you do it with humour?

P: Yes, well I did it … here I am, I’m PW Botha, and I had the first virus in my life, which was called apartheid, and there is a second virus, which is called HIV. And for both of them there was no cure, except care. If you cared about the [inaudible] of apartheid, you could solve the problem. If you care about the life that is threatened through a virus, and the same happens with Ebola – dis dieselfde storie nou, so ek gaan terug met nog ‘n ander kiemetjie wat sit in my hare. And it took … and I mean I just went sometimes three schools a day, sometimes seven schools a week. I mean, it just was an obsession with me that I go from first world to second world to third world schools, and those mean schools that are blikhuisies en ons sit onder ‘n boom en daar’s die koei.

R: But then you must believe that you have a role, that it is more than just a performance?

P: Oh no, I know I have a role. I know that I … thinking back to my school days at Nassau Hoërskool in die Kaap, when CAPAB sent a troop of actors with our setwork plays, set books. Wim, Limpie Basson, ai man! Die wonderlikste mense. Cobus Rossouw.

R: Sandra …

P: Dit was voor Sandra! Sandra was nog hier.

R: Nee, Cobus se vrou.

P: Sandra Kotze! Yes, and they would come and they would do like 20 minutes from our setwork and make it so alive! And we have never forgotten that. We never forgot that. I remember what they wore, what they said … And I knew that if I go to a school with my entertainment and actually entertain these kids about the future and make then excited about the fact that they are responsible for what happens to them at the school, they need that education to actually change the world. They will never forget it. And I use words when I talk about sex, I use words. I said to them: “You know, when I was your age nobody talked about sex. It was totally unspoken about, we were told about the birds and the bees … ”

R: If at all!

P: “Do people talk about the birds and the bees?” I said: “Listen, how does a bird fuck a bee?” You say that word in the school hall, and I mean, I have seen teachers go white – the black teachers go white! The kids, well, first of all, they will listen to every word I say after that. And I said to them: “You’re not going to hear that word again. I’m not here to do a demonstration of free speech, but I want you to know where the minefield is. That is where the minefield is! Now, you are in charge of your future. Saturday night, you’re going to go to a party and you all look like small convicts here in your uniforms, you look 12, you’re not 12, at the party you are going to look 24. You’re going to look great! You’re going to look very sexy, and sex is very exciting, it’s very nice. Don’t do it now, because you really, truly have got other things to do. So think about this very carefully. Make your decision. Do you take drugs? I say come on man, you do dagga! I’m not telling you not to, I’m just saying if you take a drug, can you think clearly? No. And then I say okay, you can’t think clearly, there’s a virus, you make one mistake and your life changes forever.” The kids are not stupid!

R: And it is actually a very simple message if you address it directly.

P: And you don’t even address them. You share it with them! We’re in the same lifeboat here. Not all of them are convinced – sometimes the parents complain and I am very careful not to paint the teachers into a corner, because they can’t speak like that. Teachers unfortunately can’t. And they’re so relieved, they say: “Thank heavens you’ve been here. We can say: ‘Do you remember what Oom Pieter said last week?’” You would be talking about that thing.

R: Changing the subject completely. Tell me about your move to Darling? Why Darling?

P: Well it was a public holiday that wasn’t a public holiday in 1995. It was the old Ascension Day, Hemelvaart Dag. Beautiful day, and I thought I’m just going to … Somebody said McGregor is so pretty, I’m going to look at McGregor. En ek klim in die kar … Went to, drove, drove, drove forever. And where the hell am I now? I mean, Darling? What the hell did I do here? I took a wrong turn. It’s like going to China and ending up in Brazil! It couldn’t have been more ridiculous. I remember the last time I was in Darling was when I was in the navy in Saldana, when we came through to go home to Cape Town for a weekend off and the bus stopped at the Darling railway station where we had a meat pie. Now I own the railway station, how’s that! And in toeka se dae pa used to drive us in an Austin Prefect to drive to Darling to look at the blomme. And that was a journey that took four hours in those days, from Cape Town. There was a little restaurant in Darling that did Schnitzels, and I had a Schnitzel but I was too early so the man said go and look around a bit and come back in an hour. And there was a lady outside selling her house, and she’d been at my show at the Baxter the week before and she said: “What are you doing here?” And I said I was supposed to be in McGregor and she said: “Not McGregor. Get in the car and I will drive you around.” Fine. So she drives me in the pretty town, and she said: “There’s one house we’re selling, it’s an open day, it’s an impossible house, it’s been empty for seven years. It’s a mess.” And I should go down next to the NG Kerk en daar, next to all the [inaudible] is this old Victorian house with a few shutters. It’s like an old lady with no teeth. And I just thought: “Aaaah! I must have this house.” So I bought it in the car.

R: Why? What does that …

P: I don’t know. Now I can tell you what it was: Instinct. I also learned: Never ignore your instinct. You don’t understand it, but you ignore it at your peril.

R: But what is it that caught your heart?

P: Just old Victorian House, overran. I have no idea! Die gogga het gepraat, hier agter. The little green man. Anyway, so I bought the house. I went back to Cape Town and I said: “I bought a house in Darling.” And people said: “You’re mad!” You know how good that is? Mad? It means nobody has thought about it. If they had said: “Great!” they would have thought about it and then they have fingerprints on what you have done.

R: Where were you living before?

P: I was living in the Gardens. I just bought a house in the Gardens, I mean, why do I need another house? In fact, I went back the week afterwards to say: “Listen, I made a mistake.” And as I sat in front of the house and I looked at it and I thought: “Jirre, die is ‘n gemors!” A little car stopped and a big blonde boy in jeans got out and he said: “You’ve just bought this house and I just wanted to say jis … I restore Victorian houses, I have just come from London. Can I do this house as a showcase?” What can I say? And then six months later when the carpenter was moving out of Darling – and he used the old station, the abandoned station, as his little studio, they said: “Can we use the old station as a store room vir Evita se skoene?” So they said: “Ja, R70 per month rental.” But the moment I stood there next to the railway line and the train rattled through, I thought: “Wag ‘n bietjie – Evita se Perron!” Perron is Afrikaans for station platform. And Evita Peron. Evita Bezuidenhout! So we built a little stage, and for a year we had a show on every Sunday at 12:00. We didn’t have a dressing room, so I used to put Evita together in my house, opposite the NG Kerk, and when Evita left the house being blaffed at by the dogs, the church came out. And the people would come out of the NG Kerk as Evita got into the car and say: “Mevrou Bezuidenhout! Welkom, ons is so bly jy is hierso.” En die dominee kom skud hand and I thought: Where in the world. Where in the world! So of course the name of the town is Darling, which is of course English for Skattie, and it’s nearly 20 years old. Next year we’ve been there for 20 years.

R: You set up Evita se Perron with minute attention to detail. What went into that? I mean, once I spent a very happy morning there one day, just wandering from one thing to the other!

P: It was a work in progress. It started as this one little place, and then we built on the second venue, which is of course the restaurant theatre, but we’ve got the small little venue which we also can use for various things, we’ve got a cinema there. And then I’ve been collecting all this boere kitsch – since the days at the Market Theatre in the early 1980s. Bloedrivier, jy weet, al daai prente. En …

R: Why, what attracted you to it?

P: It’s my background! You know, people laugh at it en dit het niks met my te doen nie maar dit het baie met my te doen. Pieter Uys, is Pieter Uys en Dirk Uys, die twee Voortrekker leiers. That’s why I put a hyphen between my two names, to really piss off the Broederbond, you see. And so I really have no shame about the fact that there was a history, I don’t like most of what happened at the expense of so many people, but it’s there! You can’t have a revision and pretend it wasn’t there. But I thought … En Dawie Malan! My wonderful friend Dawie Malan, who was my director and we worked together aan die Van Aardes van Grootoor.

R: We were at school together.

P: Dawie is, jy weet, dis 30 jaar vandat hy weg is, nê. Ons dink baie aan hom, gedurig. I think about him all the time. Anyway, Dawie always loved the fun of that kitsch. And of course, Van Aardes was inspired by all that Boere Kitsch of the old radio serials. The Du Plooys from Soetmelksvlei. So I started collecting these things, and I also had a huge collection of letters, that as a little boy I got from my heroes. Mrs. Hendrik Verwoerd, and president Swart, all saying: “Jy’s ‘n oulike kindertjie en jy het pragtig gesing en die Here sal jou seën en doktor stuur liefde.” And I had that, so I framed these things and put them up on the wall and I just thought it’s bloody nonsense, people will laugh. I don’t know what. And slowly it developed into what is now the Museum, or I call it the Nauseum. Of all these images from the apartheid era. And you know the most extraordinary thing is people, it’s quite a significant thing. I sit in the dressing room, I can hear as people go through and I hear the old people, die ouma en die oupa, passing Hendrik Verwoerd, passing the Bloedrivier ding and all these kitsch things. “Ag mamma, kyk daar! Dis Oom Hendrik. Ag pappa, kyk, onthou jy dit!” En hulle raak bewoë, nê, emotional. Now their children, the parents of the grandchildren, sê: “Ag ma! Ag asseblief! Ek wil nie kyk na hierdie nonsens nie!” And the grandchildren, die klein meisietjie, ek hoor, sy sê: “Ouma, wat beteken ‘Whites Only’?” Now that 80 year old Afrikaans Christian granny, a good woman, for the first time, has to make sense for herself what it means. She’s never had to think about it. She has to explain. That’s what it’s all about for me. Because there’s no agenda, there’s no description of anything. I don’t tell them what’s good or bad. The Whites Only sign from the airport … ag from the stations en die goed. I had to actually put another little sign on, saying this is a pre-1994 sign, because the black guests don’t go in there! It’s 2014! You can go in there! “No, no, no. That’s fine.” The pain doesn’t go away.

R: And there’s an almost genetic memory.

P: And the people really enjoy those signs. The black father, the white mother and the brown child – they stand like this for a photograph. So the humour is again the underlying thing, and it is … ja. But it is a work in progress, constantly.

R: And your own home? What makes a home for you?

P: Privacy. That’s it. It’s my place. It’s my … and I meet many, many people at the Perron, and I say I’ll meet you at the Perron. “Yes, but we’d like to come to your house.” And I say: “Yes, you can come to my house, but let me meet you at the Perron, because that’s the sort of the …

R: The public face.

P: Ja, en dis lekker en dis so. My home is … I grew up in Pinelands in this lovely house with my family, I had a wonderful family life. And then I’ve always had lovely homes in Jo’burg – in Melville, always in Melville, which I enjoyed hugely.

R: Are there any objects that you take with you?

P: Usually things I can roll up, things from the wall. Pictures. In the old days LPs, which weighed a ton – dankie Vader, we can now all put it on something this big! Isn’t it wonderful, all your stuff! You don’t have to take lorries to carry it around. So I sort of try to lessen the burden of stuff. Now, what I have to do, is just make sure that my work is very clearly focused and filed. I’m a very good organiser. I have to be, because I’m my own producer so I have got to work very carefully, so everything that I’ve done has got its own file and everything in there. If you say to me about Van Aardes van Grootoor, I just get a box and everything is in there. Van censor board to whatever. Ja, so I’m really interested and excited to just see where the next step is going to be, because every day you think: What is happening now? Where do I take this crazy little train that I put everybody on, so it’s a lovely journey.

R: Well we will watch with great interest, and good luck and steam ahead!

P: Steam ahead! Dankie.

R: Thanks for being here.

P: Dankie Darling.

* This interview was first published on 11 December, 2014

Leave a Reply